Introduction

Symptoms of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency have considerable overlap with those seen in other neurological disorders, which can lead to misdiagnosis. The infographics on this page describe clinical features present in both AADC deficiency and more commonly seen conditions — cerebral palsy, epilepsy, neuromuscular disorders and mitochondrial disorders — alongside important differentiating signs, to help you to make an accurate, timely diagnosis.

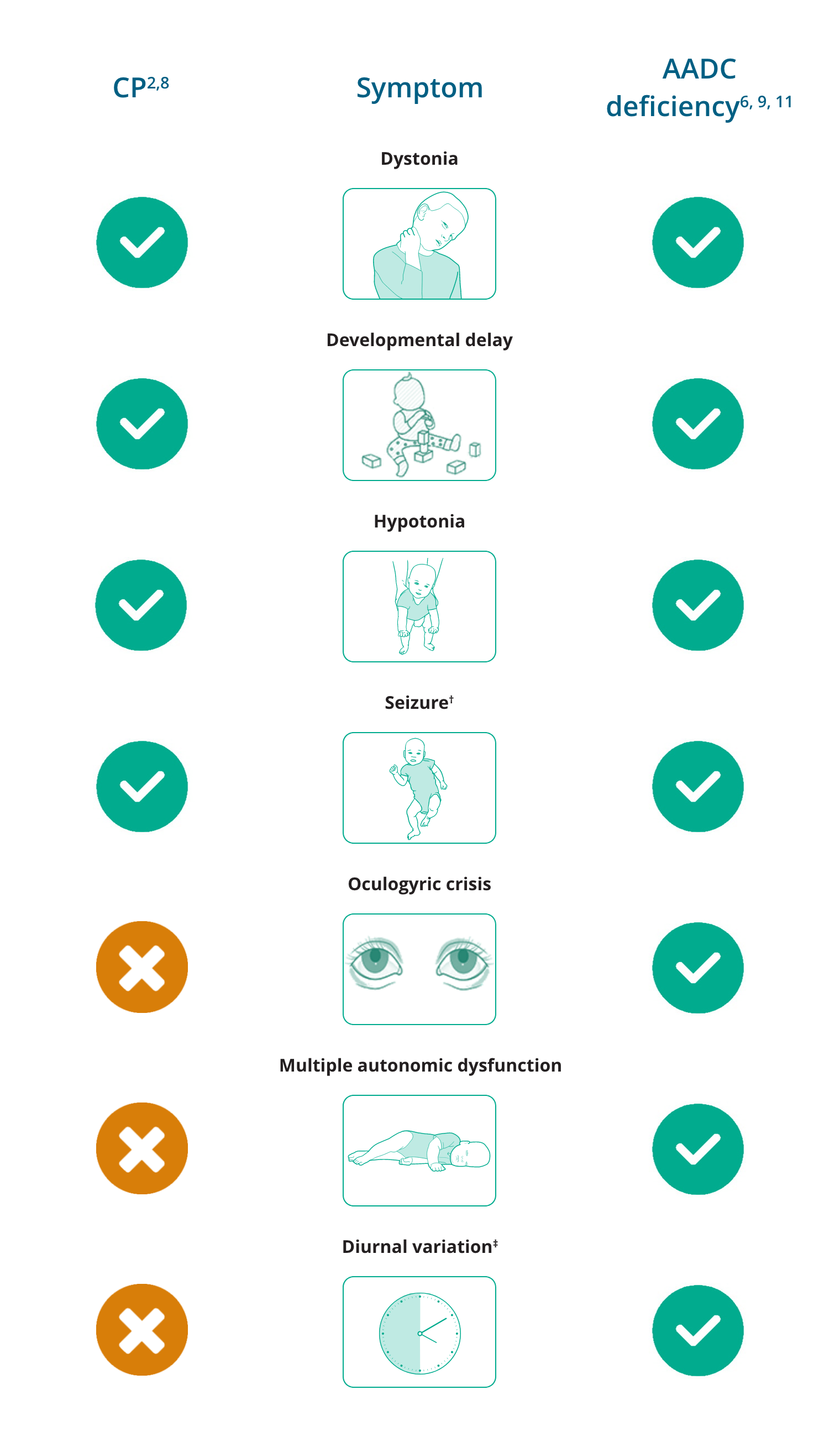

Differential diagnosis of AADC deficiency: Cerebral palsy

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of permanent neuromotor disorders causing activity limitation that are attributed to non-progressive disturbances that occur in infancy or early childhood, accompanied by developmental delay.1,2 It is the most common physical disability in children, with a prevalence of 1.7–3.1 cases per 1,000 in high-income countries.3

There are several forms of CP, classified according to which part of the central nervous system is damaged and the different manifestations:4,5

- Spastic CP is the most common form of the disorder,

occurring in >70% of cases. Symptoms include stiff, spastic muscles, abnormal movements, difficulties controlling and coordinating muscle movements, impairment of oral, lingual, and palatal movement, resulting in dysarthria and dysphagia. Consequently, failure to reach normal milestones for sitting, crawling and walking results.4,5 - Athetoid or dyskinetic CP occurs in ~20% of cases and is characterised by slow, writhing movements (athetosis), repetitive, twisting motions (dystonia), and unpredictable, irregular movements (chorea) that can all range from slow to rapid and can be accompanied by pain. Movements may increase with emotional tension and can disappear during sleep.4,5

- Ataxic CP occurs in less than 5% of cases.

Symptoms include weakness, poor coordination, tremors and shaky movements, unsteady balance, and difficulty with rapid or fine movement.4,5 - Mixed CP is a common occurrence whereby patients present

with a combination of symptoms, but generally it includes spasticity and athetosis.4,5

Many of the childhood manifestations of CP are similar to those seen in patients with a monoamine neurotransmitter disorder such as AADC deficiency, often leading to a misdiagnosis of CP.6 Consequentially, the term “CP mimic” is used to describe a number of neurogenetic disorders that manifest similarly in early childhood.2

Key distinguishing clinical symptoms of AADC deficiency that are atypical in CP

are oculogyric crises and diurnal variation of motor symptoms. Appropriate investigations, including analysis of neurotransmitters in cerebrospinal fluid, are essential for an accurate clinical diagnosis.2,7

CP mimics also show several features that differ from classic CP and can serve as diagnostic clues, including multiple features of autonomic dysfunction. Features of autonomic dysfunction include excessive sweating (diaphoresis), temperature instability, profuse nasal and oropharyngeal secretions, poor gut movements (gastrointestinal dysmotility) and sleep disturbances.2

Brain MRI is a first‐line investigation in a child or adult with an undiagnosed motor disorder which suggests CP. Brain imaging can readily reveal a cerebral malformation as the main cause of neurological symptoms. Aside from cerebral malformation, brain imaging can reveal either normal findings or specific lesions which are characteristic of a genetic disorder or group of disorders, which should prompt further investigation.2

Overlapping and differentiating symptoms of CP and AADC deficiency*

- Novak I, et al. JAMA Pediatrician. 2017; 171: 897–907.

- Pearson TS, et al. Mov Disord. 2019; 34: 625–636.

- Monbaliu E, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2017; 16: 741–749.

- Cerebral Palsy Guidance. Cerebral Palsy Symptoms. Available from: https://www.cerebralpalsyguidance.com/cerebral-palsy/symptoms/. Accessed February 2021.

- Cerebral Palsy (CP) Syndromes. (n.d.). Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Available from: https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/neurologic-disorders-in-children/cerebral-palsy-cp-syndromes. Accessed February 2021.

- Ng J, et al. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:567–584.

- Kurian MA, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10:721–733.

- Hallman-Cooper JL, Gossman W. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2019. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538147/. Updated July 18, 2019. Accessed February 2021.

- Zouvelou V, et al. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019; 29 (3): 427–437.

- Manegold C, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:371–380.

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

- Gururaj AK, et al. Seizure 2003;12:110–114.

- Singhi P, et al. J Child Neurol. 2003;18:174–179.

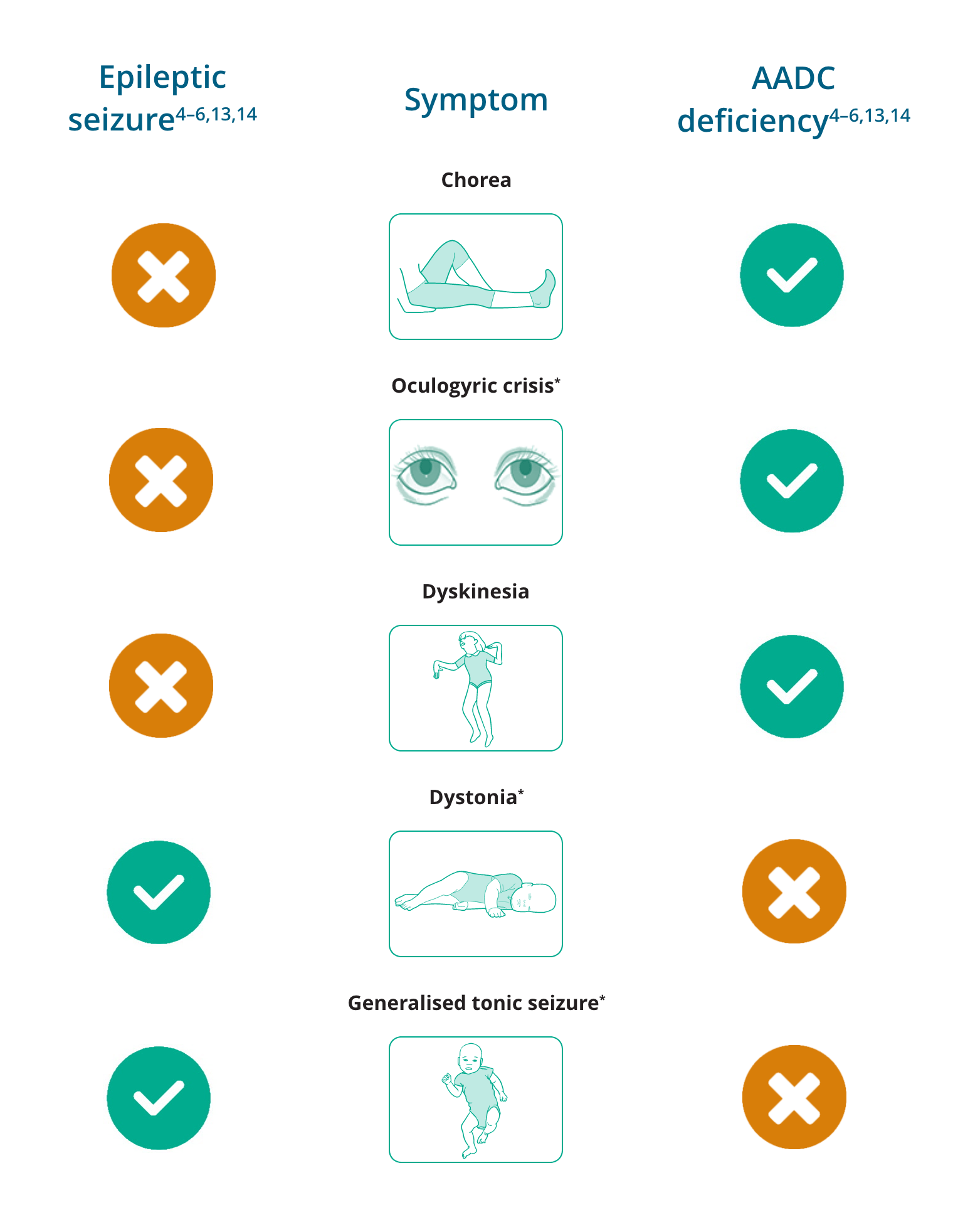

Differential diagnosis of AADC deficiency: Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterised by recurrent and unpredictable seizures due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.1,2

It is one of the most common neurological diseases in the world, affecting around 50 million people of all ages.2

Epileptic seizures are divided into three categories:3

- Generalised seizures begin in bilateral, distributed neuronal networks and are comprised of absence, generalised tonic-clonic (GTC), myoclonic, and atonic subtypes

- Focal seizures originate in neuronal networks limited to part of one cerebral hemisphere and the clinical manifestation depends on the area of cortex involved

- Epileptic spasms are characterised by sudden extension or flexion of extremities that are held for several seconds and reoccur in clusters

Paroxysmal events that often develop in patients with AADC deficiency, such as oculogyric crises, tonic or dystonic posturing of the limbs, myoclonus and chorea, can mimic epileptic seizures and, consequently, can be misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures.4–8 As a result, patients often receive multiple antiepileptic drug treatments without response before receiving a diagnosis of AADC deficiency.8 Notably, EEG findings tend to differ between patients with AADC deficiency and patients with epilepsy, and an ictal EEG analysis is key for differentiating between patients experiencing paroxysmal events and those with epilepsy.4

Epileptic seizures are uncommon in patients with AADC deficiency,5 although a few cases have been reported.4,9–12 Based on the limited number of case reports, epileptic seizures tend to occur in the first few years of life, are not severe, are of the GTC or complex focal subtype and, where documented, have been well controlled with administration of conventional anti-epileptic drugs.4,9–12

The differentiation of epileptic seizures from non-epileptic paroxysmal events using EEG analysis is critical to prevent misdiagnosis of AADC deficiency as epilepsy and to ensure the appropriate management of patients.4

Differentiating signs of epileptic seizures and AADC deficiency

*Oculogyric crises have been reported to be present in 97% (n=30/31) of patients with AADC deficiency aged 2–12 years13

†Dystonia may, uncommonly, appear as a sign of rare epileptic disorders14

‡Generalised tonic seizures are not typically seen in AADC deficiency, but have been reported in a small number of patients with AADC deficiency who have also been diagnosed with epilepsy6

- Fischer RS, et al. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):520–530.

- World Health Organization. Epilepsy: a public health imperative. 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/neurology/epilepsy/report_2019/en/. Accessed February 2021.

- Stafstrom CE, Carmant L. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5:a022426.

- Ito S, et al. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:876–878.

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

- Pons R, et al. Neurology. 2004;62:1058–1065.

- Brun L, et al. Neurology. 2010;75:64–71.

- Lee WT. Epilepsy & Seizure. 2010;3:147–153.

- Swoboda KJ, et al. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(Suppl 6):S49–S55.

- Hsieh H-J, et al. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:517.

- Anselm IA, Darras BT. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;35(2):142–144.

- Manegold C et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:371-380.

- Pearson T, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43:1121–1130.

- Orphanet. Progressive myoclonic epilepsy with dystonia. Available from: https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Expert=352596&lng=EN. Accessed February 2021.

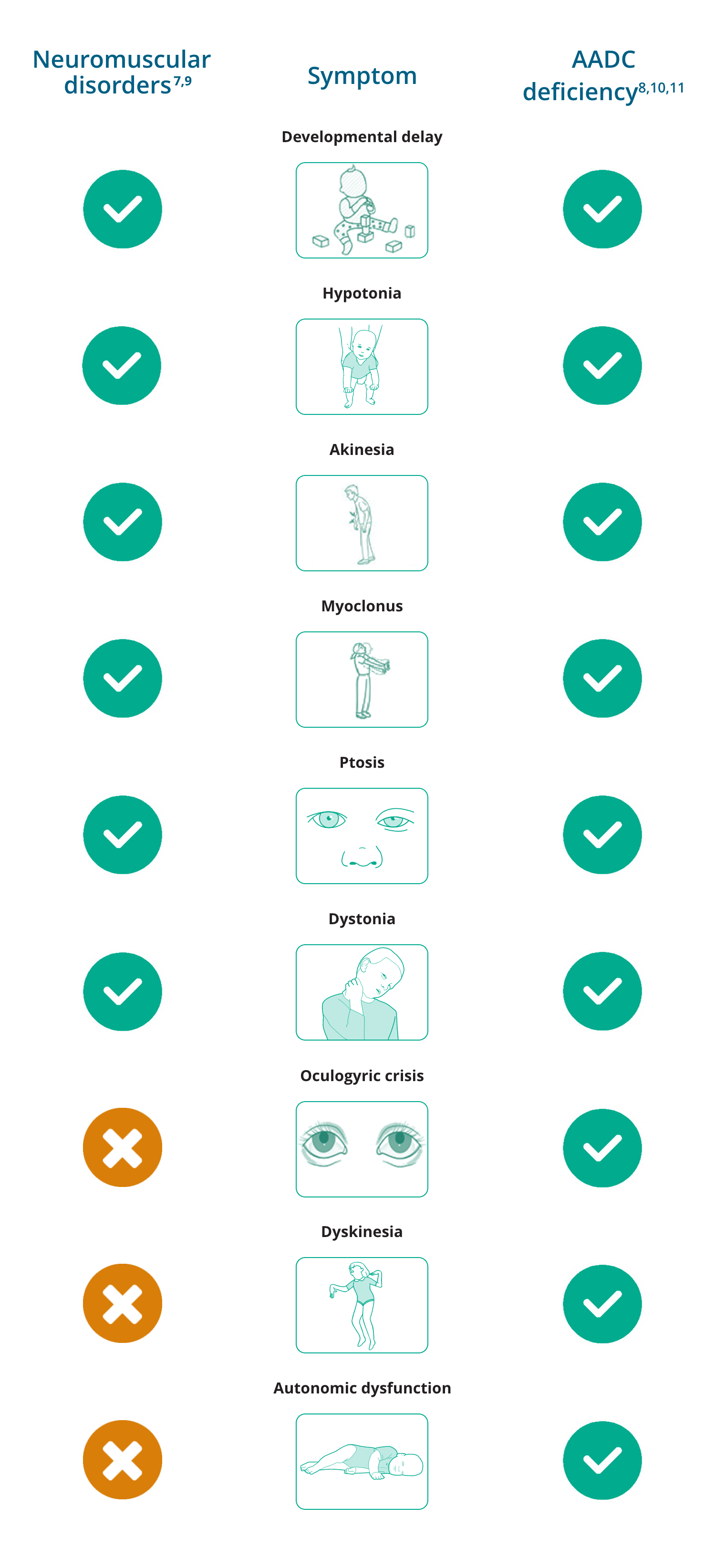

Differential diagnosis of AADC deficiency: Neuromuscular disorders

Neuromuscular disorders are a broad group of genetic heterogeneous diseases that impair muscle and/or the peripheral nervous system.1–3 Types of neuromuscular disorders include:1,4

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

- Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease

- Multiple sclerosis

- Muscular dystrophy

- Myasthenia gravis

- Myopathy

- Myositis, including polymyositis and dermatomyositis

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Spinal muscular atrophy

Impairment can arise in cell bodies (as in ALS or sensory ganglionopathies), axons (as in axonal peripheral neuropathies or brachial plexopathies), Schwann cells (as in chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy), neuromuscular junctions (as in myasthenia gravis or Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome), muscle tissue (as in inflammatory myopathy or muscular dystrophy), or at any combination of these sites.5

Neuromuscular disorders vary in disease course and severity,6 depending on the body area affected but typical symptoms include muscle weakness, abnormal or impaired ambulation, joint contractures, skeletal deformities, altered sensory perception (in neuropathies) and respiratory failure.1 Myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, and fatigable weakness may occur with normal intervening muscle function, or in individuals with persistent neuromuscular manifestations.1

Since 50% of AADC deficiency patients present with movement disorders (hypokinesia, chorea, dystonia, ballismus, dyskinesia, tremor, myoclonus), AADC deficiency can mimic many neuromuscular disorders, such as congenital myasthenia gravis, leading to misdiagnosis.7,8

Overlapping and differentiating symptoms of neuromuscular disorders and AADC deficiency

- Dowling JJ, et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2018;176:804–841.

- van Putten M, et al. Dis Model Mech. 2020;13:dmm044370.

- Mary P, Servais L, Vialle R. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104:S89–S95.

- Deenen JC, et al. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2015;2:73–85.

- Morrison B. Semin Neurol. 2016;36:409–418.

- Sáez A, et al. J of Biomedical Optics. 2013;18:066017.

- Kurian MA, Dale RC. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016;22(4):1159–1185.

- Ng J, et al. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11,567–584.

- Kaler J, et al. Cureus 2020;12(2):e6922.

- Manegold C, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:371–380.

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

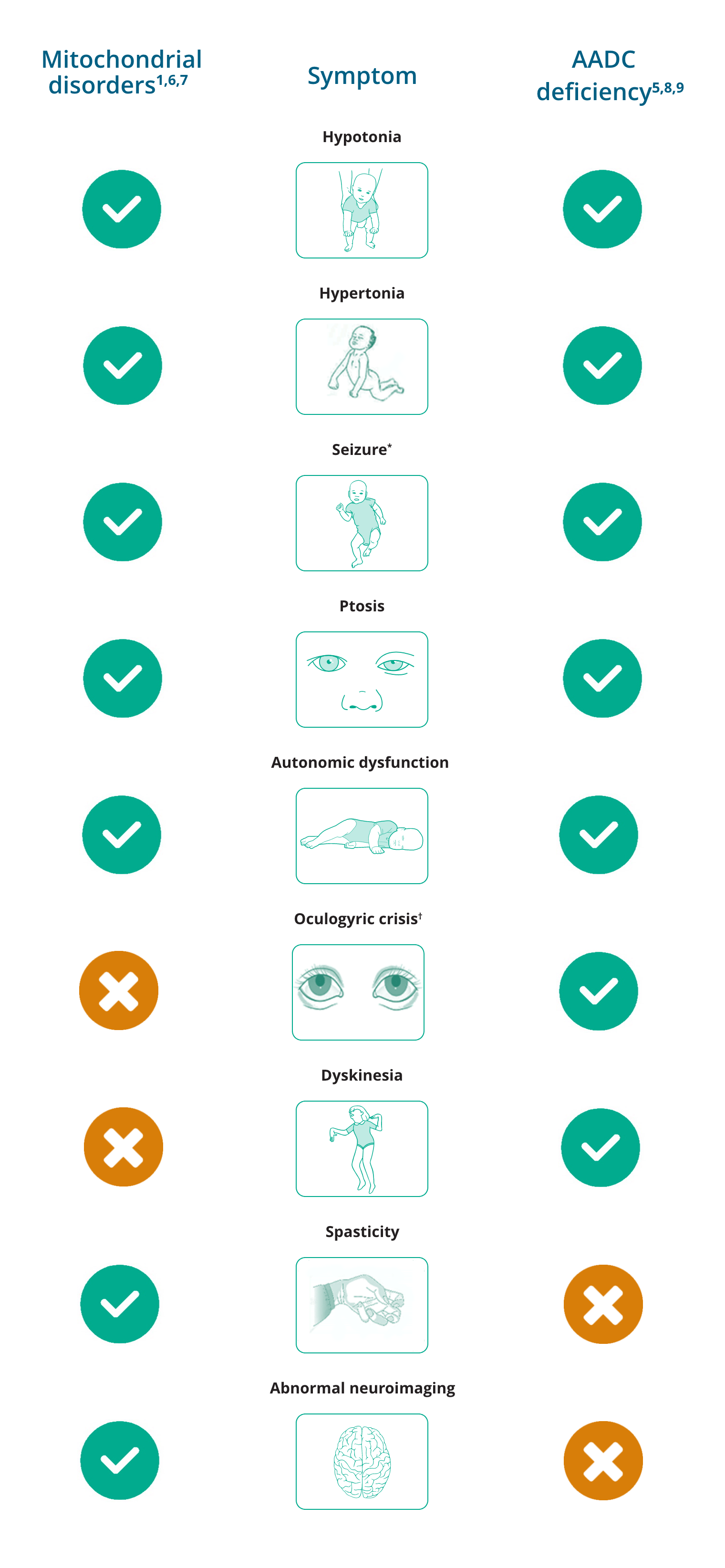

Differential diagnosis of AADC deficiency: Mitochondrial disorders

Mitochondrial diseases are a clinically heterogeneous group of disorders that arise as a result of dysfunction of the mitochondrial respiratory chain.1 The estimated prevalence of mitochondrial diseases was found to be at least 20 per 100,000 in the population.2

Common clinical features of mitochondrial diseases include ptosis, external ophthalmoplegia, proximal myopathy and exercise intolerance, cardiomyopathy, sensorineural deafness, optic atrophy, pigmentary retinopathy, and diabetes mellitus.1

Mitochondrial disorders and their primary clinical features1

| Mitochondrial disorder | Primary clinical features |

| Alpers-Huttenlocher syndrome |

|

| ANS (including SANDO and MEMSA*) |

|

| CPEO |

|

| KSS |

|

| Pearson syndrome |

|

| LIMM (fatal and non-fatal forms) |

|

| Leigh syndrome |

|

| NARP |

|

| MELAS |

|

| MEMSA* |

|

| MERRF |

|

| LHON |

|

ANS, ataxia neuropathy syndrome; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; CPEO, chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia; KSS, Kearns-Sayre syndrome; LIMM, lethal infantile mitochondrial myopathy; LHON, Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes; MEMSA, myoclonic epilepsy myopathy sensory ataxia; MERRF, myoclonic epilepsy with ragged-red fibres; MIRAS, mitochondrial recessive ataxia syndrome; NARP, neurogenic weakness with ataxia and retinitis pigmentosa; SANDO, sensory ataxic neuropathy, dysarthria, ophthalmoplegia; SCAE, spinocerebellar ataxia with epilepsy.

*Also referred to as MIRAS and SCAE.

In infants, clinical features such as hypokinetic rigid syndrome and generalised dystonia can mimic those seen in AADC deficiency and other paediatric neurotransmitter disorders, making diagnosis difficult based on clinical presentation alone.3 The presence of oculogyric crises may help to differentiate AADC deficiency from a mitochondrial disorder, however, this is not sufficient to make a definitive diagnosis as oculogyric crises may present in mitochondrial disorders.4 Therefore, molecular genetic testing is warranted to confirm or rule out a diagnosis of AADC deficiency.5

Overlapping and differentiating symptoms of mitochondrial disorders and AADC deficiency

*Seizures are uncommon in AADC deficiency but have been reported.

†While oculogyric crisis has been reported, it is not typical of mitochondrial disorders.

- Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al (Editors). GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2020.

- Schaefer AM, et al. BBA. 2004;1659:115–120.

- Marecos C, Ng J, Kurian MA. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2014;37:619–626.

- Garcia-Cazorla A, et al. Mitochondrion/ 2008;8:273–278.

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

- Garcia-Cazorla A, et al. Mitochondrion. 2008;8:273–278.

- Ng J, et al. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:567–584.

- Manegold C, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009;32:371–380.

- Gropman AL. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10:273–285.

What is Juvenile parkinsonism?

- Juvenile parkinsonism is a rare movement disorder with symptoms that present before the age of 211

- Juvenile parkinsonism is a relatively rare syndrome1

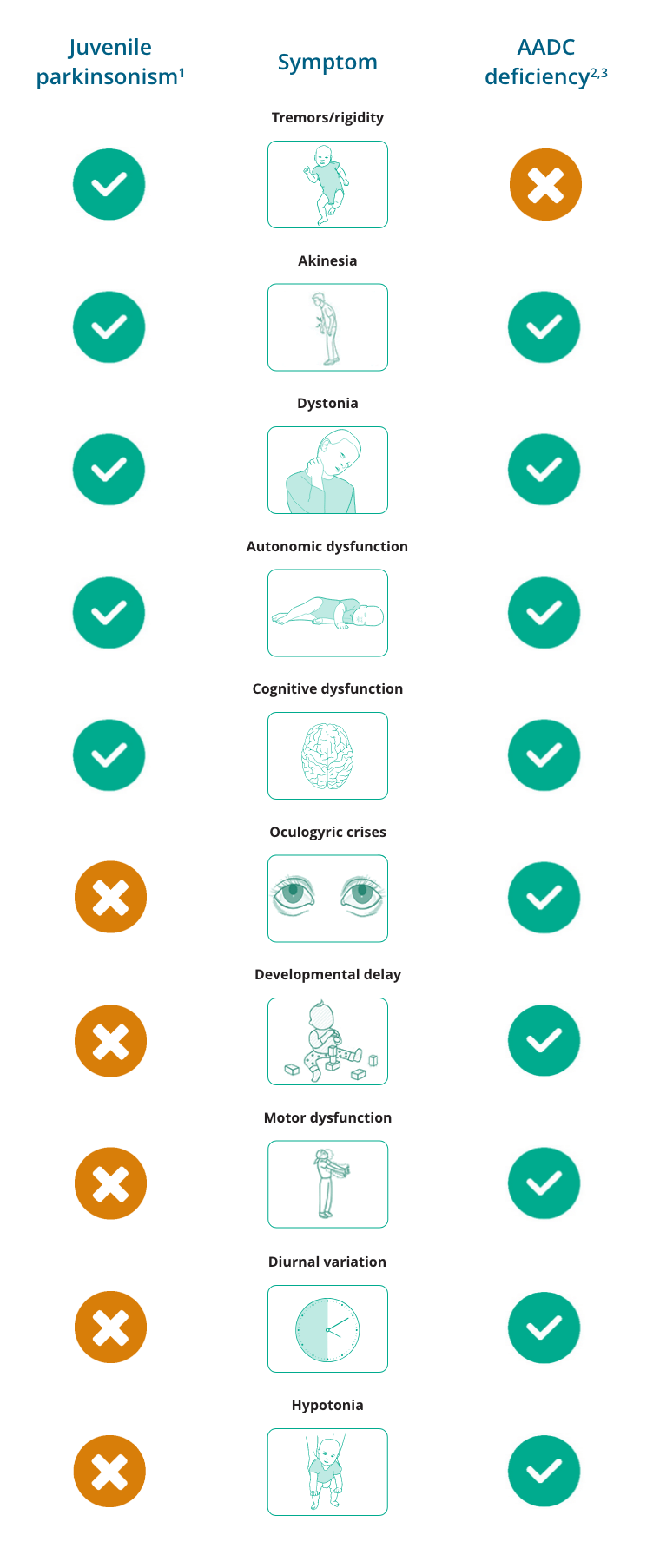

Overlapping and differentiating symptoms of juvenile parkinsonism and AADC deficiency

- Patients with juvenile parkinsonism have prevalent dystonia and less incidence of cognitive deterioration and postural instability1

- The distinctive features of Parkinson’s disease are tremors at rest, rigidity, bradykinesia and loss of postural reflexes1

- Bradykinesia is a cardinal feature of Parkinson’s disease that overlaps with AADC deficiency1,2

- Other symptoms that appear in juvenile parkinsonism may also appear in AADC deficiency, such as dystonia, autonomic dysfunction, and cognitive delays1,2

- Thomsen TR, Rodnitzky RL. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:467–477.

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

- Hwu P, et al. EMBO Mol Med. 2021;13:e14712

Explore interactive clinical case studies

Suspect AADC deficiency? Act now

• Tests to diagnose patients with AADC deficiency often show elevated plasma 3-OMD levels1–3

• Earlier diagnosis may be achieved by dry blood spot testing for 3-OMD4,5

Find out more about 3–OMD testing now at: AADCDtesting@ptcbio.com

- Wassenberg T, et al. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:12.

- Chen PW, et al. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;431:19–22.

- Brennenstuhl H, et al. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2020;43:602–610.

- Hyland K, Reott M. Pediatr Neurol. 2020;106:38–42.

- Chien YH, et al. Mol Genet Metab. 2016;118:259–263.